The Mediterranean Sea is the largest of the semi enclosed European seas: its basin area covers almost 2.6 million km2 , 0.82 % of the world’s ocean surface. Surrounded by 22 countries and territories from Europe, Africa and the Middle East that share a coastline of 46 000 km, it is connected to the Atlantic Ocean through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, to the Red Sea by the man- made Suez Canal and to the Black Sea via the Bosphorus Strait. The Mediterranean region is home to around 480 million people living across three continents: Africa, Asia and Europe. Often called the ‘cradle of world civilization’, the Mediterranean basin has a long history, and an extremely rich natural and cultural heritage.

It provided an important ancient route for merchants and travelers, allowing for trade and cultural exchange between people in the region. It is still one of the world’s busiest shipping routes: about one third of the world’s total merchant shipping —or ~ 220 000 merchant vessels of more than 100 t —cross the sea each year. In addition, over the last few years Mediterranean ports have begun to compete with one another in the strive to increase their share of traffic. The strongly fluctuating nature of the maritime shipping sector and the increasingly narrow profit margins make this tendency extremely threatening for the future of the Mediterranean Sea.

A

The Components of Maritime Transport in the Mediterranean

There are several dimensions of maritime traffic in the Mediterranean, which can be considered on three levels:

• As a ‘maritime route’ that, as such, is one of the world’s major trade routes, through which nearly a third of world trade ‘passes’, from the mouth of the Suez Canal to the Straits of Gibraltar or the Bosporus, from the Atlantic to the Black Sea.

• As a ‘crossroads ‘of continents –European, Asian and African– whose trade is growing with globalisation.

• As a ‘landlocked sea’ through which coastal countries develop their trade.

A

Mediterranean Ports’ competences and competitions

The Mediterranean is an especially appropriate area for transport trade. The main global maritime route crosses the Mediterranean Sea from Suez to Gibraltar; one of the centers of the global economy is situated on the Northern shore of the Mediterranean; and the EU is opening its doors to new members. Moreover, emergent economies are located in the Northeast connected with the Black Sea and Africa. They have a potential of development and strong links with European economies through Mediterranean seaports. The optimal routing decision tends to be cargo shipping through hubs, as the hub charge has decreased and its efficiency improved . All of these aspects are catalysts for the growth of the well-defined seaports on the Northern shore, in order to establish a competence between them, to attract and generate new traffic and to develop new harbors on the Southern shore coast.

Harbors like Ceuta, Tangier, Djen-Djen, Bizerte, Damietta or Port Said are a new generation in the Mediterranean and will surely change the map of transport and economy in the South Mediterranean. A clever view will create a similar land bridge with Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, but unfortunately it will still take some decades.

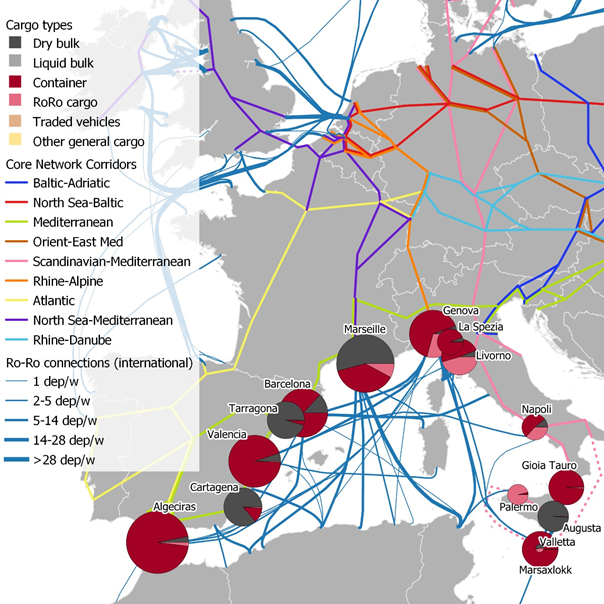

In reality, competence between harbors is not only good for the users of their facilities; but it is also good for the whole logistic line, from inland dry ports to all seaports that have been connected by the logistic lines. We can now begin to talk about competence between logistic lines, which implies alliance between economies and territories, and between modes of transport and harbors. The sustainability of a seaport is nowadays not only in its efficiency but it also lies in the productivity of the whole logistical chain. The relation between Spanish seaports such as Barcelona, Tarragona and Valencia and Italian seaports like Genoa, Livorno, Civitaveccia, Salermo or Palermo, is a very good example of the way short sea shipping can change the aspect of transport whithin the continent. It enhances the necessity of a growth in size and in the same direction between harbors.

As these chains are becoming more complex, more intricate distribution structures are needed to tailor final products in all their facets to the customer’s preferences, as Zhaojian Liu et al.5 pointed in their research. They propose options to introduce an integrated collaborative planning system where producers, retailers and logistic service providers work closely together through the sharing of information about production, sales and logistics.

To this increasing complexity, the transport logistic chain must also add environmental and security aspects that play a very important role in the definition of the whole transport system. It may leave out of the line the seaports that will not adapt their characteristics to international regulation on these matters.

In short words, it can be concluded, that the complexification and changes in international trade have taken place at a very fast velocity at a global scale. The time needed to carry a good from one part of the world to another has declined, and at the same time, transport capacities have considerably grown. A ship can nowadays transport the same amount of cargo as carried by

40 ships 50 years ago, and stays only 3 days in the harbor, in contrast with the 12 days previously needed.

The growth of seaports is not enough to adapt to the accelerated rate of economical growth, but new concepts, such as logistic chains, have to be applied to understand the new relationship between peoples, territories, economies and movement of goods. The relations between the different modes of transport have also changed in the design of a harbor. There is no sustainable harbor without space to connect with a main railway, or with a logistic area inside or close by a natural part of the seaport.

Dry ports are becoming new pieces in the logistic chain, giving new opportunities to inland areas, and connecting harbors that will never be connected by sea, creating new corridors or land bridges between harbors.

The movement of all these amounts of goods, efficiently, in time, safe, and controlled, is impossible without the support of the new communication technologies, in a world where the international trade rules are not always easy.

The Mediterranean Sea transport trade is not an exception but has its own particularities, where many asymmetries are still making differences between territories, and where many considerable changes in the near future will draw new maps of relations between growing economies. Long-term strategies cannot avoid these realities, and have to play with the political uncertainties that remain in the region.

Read more here: https://www.docksthefuture.eu/mediterranean-ports-competences-and-competitions/

A

Suez Canal, and the Belt & Road Initiative: the Role of the Mediterranean countries

The BRI and the Chinese development strategy for the future The Chinese Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is probably the most important investment project worldwide since the Marshall Plan that followed World War 2 in terms of number of countries involved in the project and amount of financial resources devoted to the initiative.

Based on official statements and documents by Chinese officials and agencies, the project aims to implement the following:

1. An inland Silk Road economic belt connecting West China with Europe via Central Asia, Russia and Northeast Europe, as well as with the Indian Ocean through Pakistan. A network of railway lines, highways and pipelines will form the inland economic belt.

2. A maritime Silk Road to connect the South-eastern coastline of China to the Mediterranean Sea through the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal.

The project involves investments in port areas and inland logistic and industrial facilities along these maritime routes. The BRI was officially launched by President Xi Jinping in a speech at Nazarbayev University in Astana (Kazakhstan) in September 2013. It originally involved 65 countries11 in Asia, Europe and Africa and will be wholly completed by 2049. According to some estimates, China will spend around $1,000 billion in the next ten years to implement the initiative. The financial resources required would total around $8,000 billion over the entire investment period12. The GDP in these 65 countries considered as a whole represents around 1/3 of the entire world’s GDP and over 60% of the world’s population. Furthermore, since its launch many other countries have expressed interest in the project, by joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)13 or planning and developing transport infrastructures in cooperation with China. In fact, 48 other countries – besides the 65 countries officially involved in the BRI since its launch – have been identified so far. They are likely to become active participants in the project. As of September 2017 China had already signed cooperation agreements with 74 countries14.

The project will probably extend to other areas of the world, involving countries in Oceania and South America as well. Table 7 is a list of European and MENA countries involved in the BRI (in bold type, the countries with shores on the Mediterranean Basin). 43 European countries and 19 countries of the MENA region are involved in the BRI or have shown interest in the project. Among these, there are 22 countries with shores on the Mediterranean Basin, 13 of them are European countries and 9 of them fall within the MENA region.

The growing presence of China in the Mediterranean: economic cooperation and investments The attractiveness of Chinese investments has grown among European countries since the outbreak of the Euro crisis in 2011; over the last decade increasing Chinese investments have taken place in several Mediterranean countries. Take the example of Greece, a country heavily hit by the financial crisis, where the acquisition of the Port of Piraeus by the Chinese shipping company Cosco in 2011 was a major relief for the public budget.

Read more here: https://www.docksthefuture.eu/suez-canal-and-the-belt-road-initiative-the-role-of-the-mediterranean-countries/

A

The Mediterranean ports connectivity in the middle of a vast network of trade lanes

Short Sea Shipping (SSS) has been defined by the European Commission (1999): ‘the movement of cargo and passengers by sea between ports situated in geographical Europe or between those ports and ports situated in non-European countries having a coastline on the enclosed seas bordering Europe. Short Sea Shipping includes domestic and international maritime transport, including feeder services, along the coast and to and from the islands, rivers and lakes. The concept of Short Sea Shipping also extends to maritime transport between the Member States of the Union and Norway and Iceland and other States on the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Mediterranean’.

The European Commission has also identified two main SSS regions in Europe: a first region which includes ports located in the North Sea and Baltic Sea; a second region includes the Mediterranean and Black Sea ports. To the first region belong all the main northern European ports, in particular those of the so called ‘northern range’: ports from Le Havre to Hamburg. The second region instead includes Mediterranean and black Sea ports.

The Eastern Mediterranean (around 250 million tonnes) and the Black Sea (around 60 million tonnes) are the regions with the smallest absolute volumes, but they have also been the fastest- growing basins with 3.4% and 3.1% average annual growth between 2010 and 2018, respectively. During the same period, the EU average was 1.9%.2

Five core network corridors start/end in the Western Mediterranean basin. Four corridors (from East to West: Atlantic, North Sea-Mediterranean, Rhine-Alpine, and Scandinavian-Mediterranean) are North-South corridors linking the different ports of the Western Mediterranean with the European hinterland. The Mediterranean CNC is an exemption: it stretches from the Strait of Gibraltar along the Mediterranean coast to North Italy and on through Slovenia, Croatia and Hungary to the Ukraine.

Read more here: https://www.docksthefuture.eu/the-mediterranean-ports-connectivity-in-the-middle-of-a-vast-network-of-trade-lanes/

A

Future professional profiles in Mediterranean Ports

In 2019, a survey on the most requested professional profiles in Mediterranean ports was conducted by MEDports Association’s Employment, Training and Maritime Expertise (ETME) Committee. The survey was answered by 14 ports and 50 trainees from the Arab Academy of Science, Technology and Maritime Transport (Egypt). The survey identified profiles needed in ports in four main areas: port management, IT, environment and city port, port construction and security and safety.

The ETME Committee decided in its meeting on April 15th 2020 to continue working on this topic focusing on the future professional profiles and areas of expertise not covered by training institutes today.

Seven profiles were highlighted as very relevant by participants. These profiles are not covered or deficiently covered by current training programs. We have worked on the detailed definition of these profiles and added an additional one on Onshore-Power-Supply bearing in mind the increasing relevance of this topic.

These job profiles will be key for the future development of Mediterranean ports and they will contribute greatly to their efficiency and competitiveness in a changing environment. The adaptation by ports to new market requirements is a key element for ports’ success and their contribution to the society which may be threatened by the lack of the required training.

Therefore, we strongly invite training institutions to develop a comprehensive training offer in order to cover the needs of job profiles of the future in Mediterranean Port Authorities. Specific training modules will have to be designed for each member of the teams supporting the positions described below which belong mostly to managerial positions:

Big Data Analyst

Cybersecurity Manager

Manager of Sincromodality and Intermodal Networks

Cold Supply Chain Expert

Energy Transition Manager

Onshore-Power-Supply Manager

Circular Economy Manager

A

Impacts of COVID19 on Ports and Maritime Transport in Mediterranean Region[1]

Around 80 percent of global trade is transported by commercial shipping and intra- mediterranean maritime trade flows account for nearly 25% of global traffic volume.

The maritime industry is playing an essential role in the short-term emergency response to the COVID-19, by facilitating transport of vital commodities and products. Despite the current difficult times, a vast majority of ports have succeeded to stay open to cargo operations. However, most of them still remain closed to passenger traffic. Mid and long-term recovery will need to further enhance sustainability and resilience of the maritime transport sector as a whole, for sustaining jobs, international trade, and global economy, as much as possible.

In view of the disruption generated by the COVID-19 pandemic on the maritime networks, the Union for Mediterranean and the MEDports Association co-hosted a webinar with key sectorial partners to discuss how to enhance sustainability and resilience of ports and maritime transport in the Mediterranean region during and after the pandemic.

The Mediterranean Sea has been a critical maritime and commercial route for millennia and today. It is home to 87 ports of various sizes and strengths, serving local, regional and international markets. The COVID-19 pandemic has showcased the vulnerability of maritime networks, port efficiency, and hinterland connectivity in the Mediterranean to crisis situations. As a vital enabler of smooth functioning of international supply chains, the maritime industry should focus on building sustainability and resilience, including to ecological disasters and pandemics like COVID-19, as well as enhancing efficiency and operations, to remain viable and competitive on the global market.

It was concluded that, with due regard to the protection of public health, ports must remain fully operational with all regular services in place, guaranteeing complete functionality of supply chains. Governments were called upon to support shipping, ports and transport operators in favour of best practices. Participants reiterated that the maritime transportation system will only be sustainable as long as it provides safe, efficient and reliable transport of goods across the world, while minimizing pollution, maximizing energy efficiency and ensuring resource conservation. It was underlined that, in the maritime sector, resilience means that ports, and the organizations that depend on ports, can adapt to changing conditions and, when disruptions occur, they can recover quickly and resume business stronger than before. Furthermore, it was noted that the COVID-19 pandemic could represent an opportunity for the maritime industry to change the way the industry operates so as to effectively contribute to broader systemic resilience.

[1] https://ufmsecretariat.org/impacts-covid-ports-maritime-transport-mediterranean/